People on Ice

Starting the series with an unlikely pairing

Slap Shot

It’s the spring of 1977 in Memphis, Tennessee. Star Wars is not out yet. Elvis is still alive. My family visits a ‘50s-style diner every other week. I always get a milkshake, a licorice treat, and gaze across the street at the gates of Graceland.

I live in an apartment complex, let’s call it Dumpy Hills Apartments. Lots of young families. Me and my friends spend the days launching our bicycles off its uneven hills, treating them like ramps as we soar Evel Knievel style.

If you were an adult trying to enter the Dumpy Hills resident parking area in early March of ‘77, there’s a good chance you would’ve been mooned by a bunch of kids. You’re just going about your business, pulling your car in, and you glance off to the bushes lining the driveway, and there it is - a dozen naked kid-butts pointed in your direction. Who’s responsible for this asinine behavior?

That would be me. I was the first kid in the neighborhood to see an R-rated movie, and it was Slap Shot. Apparently, after my first viewing of the film, the image that endured for me was the team bus filled with hockey players and fans mooning their rivals. So I thought it would be hilarious to bring this new mode of visual communication to my neighbors. We only managed a couple of days’ worth of shenanigans until we were caught, and my role as ringleader discovered. I wasn’t severely punished. I think my mom was embarrassed and felt guilty about it. By exposing me to an R-rated film at such an age, I ended up doing a different kind of exposing. And my father—although I never saw his reaction—I’m certain he laughed it off.

In addition to prank nudity, I introduced the neighborhood kids to a few choice phrases. Fuckin’ machine took my quarter. Trade me right fucking now. I’m listening to the fucking song.

In my teens, Slap Shot became a recurring movie standard. Its hilarity and quote-ability made it into one of those movies that I turned several VHS tapes of into magnetic dust.

It’s also one of the first films that Gene Siskel saw in his capacity as a film critic, and one that he later admitted to being too hard on, and eventually revised his opinion of the film.

As I grew older, I was able to appreciate the more mature themes woven in amongst the f-words, violence, and nudity. Themes about the conflict between the passion for the game and the sacrifices for the business. About the integrity of competition versus the entertainment and spectacle of sport. About regrets, honesty in relationships, the compromised nature of the sports media, and the communal aspects of sports franchises.

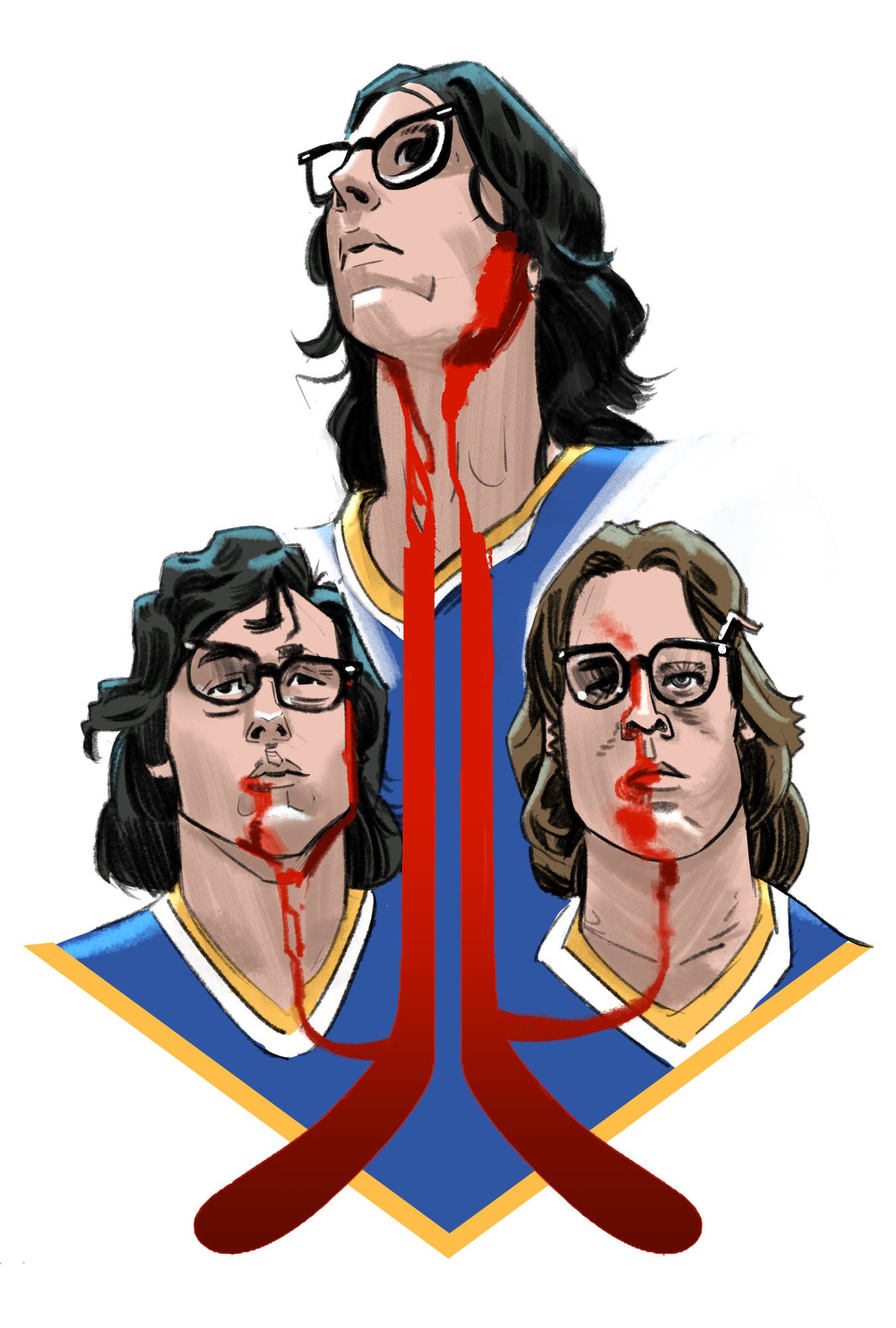

And then there’s the Hanson Brothers.

Bespectacled gangly nerds who brought their fucking toys. Who wanted to know when Speed Racer was on. Whose comedic timing were perfect, and their impressive dexterity on the ice due to the fact that they were actually real-life pro hockey players. The athlete/actors who played the Hansons went on to milk the cult fame they got from the film for years, making public appearances at hockey arenas around the world.

Few films have given me more reliable laughs across decades than Slap Shot. Comedies tend to get overlooked in film awards and top-10 lists. But those of us who love a given comedy can get obsessed—not only memorize its lines, but relish in specific line readings, especially those performed by Yvon Barrette, the actor who plays the team’s goalie. Icing happen when the puck come down, BANG, you know, before da other guys, nobody there, you know, my arm go comes out and the game stop and start up. Who own da Chiefs? Owns-uh, owns-uh.

After Life

Perhaps the first piece of speculative fiction the human race ever created was an answer to the question, “What happens when you die?”

In After Life, writer/director Hirokazu Kore-eda answers that question with a scenario where people arrive at a train station and emerge into a limbo state, held temporarily in an office where they are asked to perform a simple task that will determine how their essence moves on into the next stage of the universe.

The task in question is highly personal, so the office is staffed with afterlife counselors who help guide the souls through this ordeal with sensitivity. A warm contrast to the cold confrontational vision offered in Defending Your Life by Albert Brooks, in which Brooks is placed on trial by a hostile prosecutor and an apathetic defender.

Kore-eda cast a number of non-actors in the roles of the recently deceased, where they openly talk about their lives with candor and authenticity, in scenes that have a documentary-interview feel.

Death brings the ultimate clarity in perspective for these characters. They are empowered to reflect on the totality their lives with brutal honesty. Entire lives distilled into discrete moments.

This process is highly effective cinema. I found myself connecting to the life stories — from the likable to unlikable, the deep or the shallow — a profound empathy comes into being, and you bond with characters, some of whom have very little screen time.

The film’s premise and masterful execution causes you to reflect on your own life and how you would navigate the task put before the souls in this cosmic weigh station. This is a great film to watch with a loved one, and can inspire meaningful ‘big picture’ conversations.

It is a quiet film with a delicate pace. Emotions are restrained. Among the activities put before these people is participation in the making of a short film. The films-within-a-film are whimsically made, with simple sets and shots, but result in deeply resonant moments.

Some of the souls in this limbo find extreme difficulty in performing their assigned task. Confronting the truth of one’s life can be unbearable. There’s a special place in the universe waiting for those who cannot finish the task as well (spoiler: it’s not hell).

One can’t help but linger on the film’s fundamental question: how we would perform the task ourselves, determining our eternal fate? The task is a simple method of evaluating one’s life. I have enjoyed talking to people who’ve seen the movie to see how they would perform the task. I would be able to do the assignment, but I would not be satisfied with my result.

The best films challenge us and ask: can we change? Do we have the courage to face the forces arrayed against our desire to transform into the person we truly want to be?

I hope I can. After Life provides a simple but powerful prism through which to observe the lightwaves of our past, and refract them into a brighter future.

Good stuff, Milton!! I remember you talking about doing this. Congratulations on getting it started.