When We Were Chewing Bubblegum

We came to kick ass at the cinema

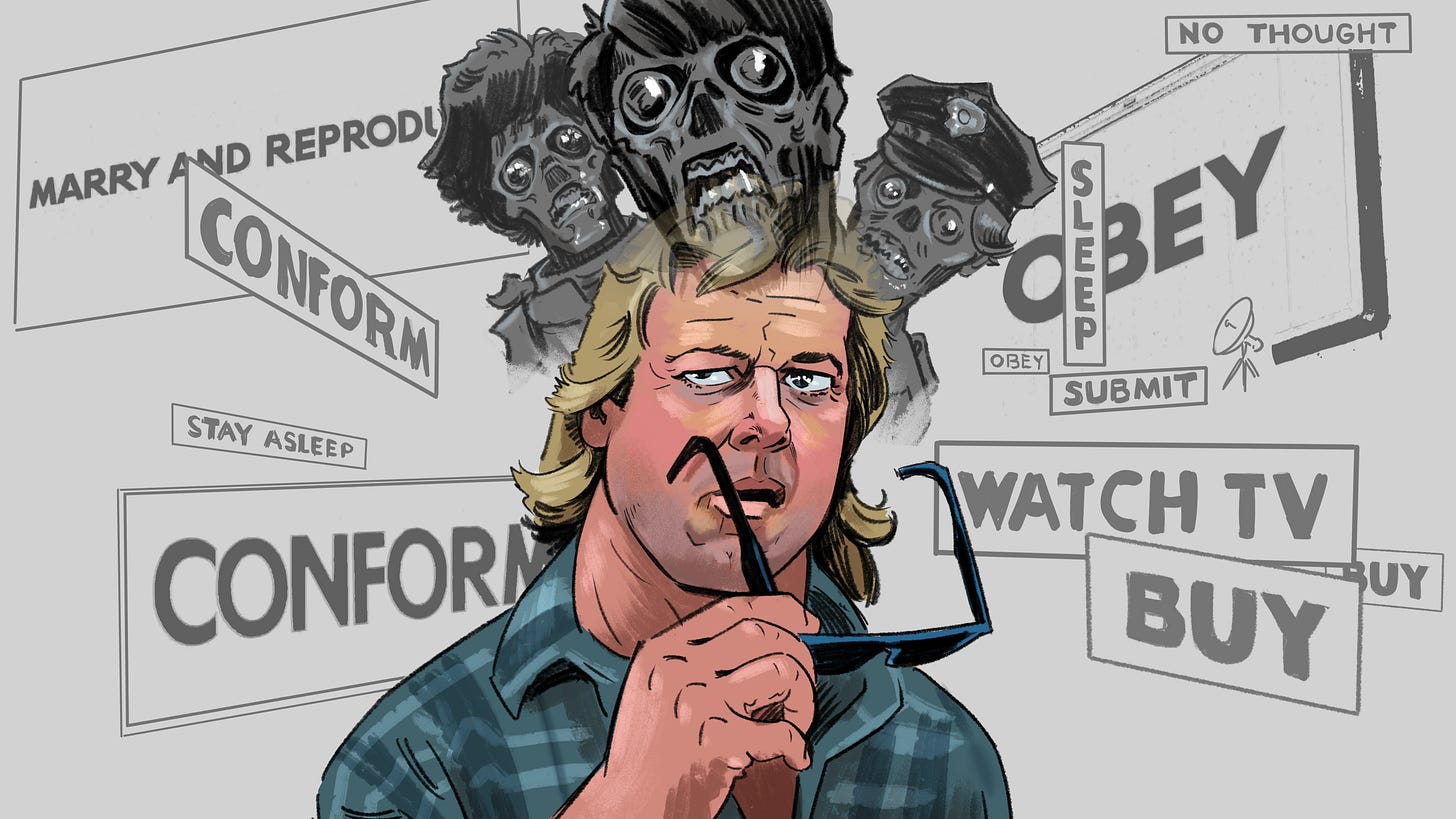

They Live

Growing up Gen-X Nerd teaches you to love the words “directed by John Carpenter.”

Halloween scares at a pure survival-instinct mode, confronting an apparition of immediate death. The Thing unnerves at a sensory-input level, making its protagonist and audiences distrust their eyes and ears. The Prince of Darkness spooks at the intersection of metaphysics and physics: summoning monsters from the realm of faith through the portal of science.

They Live terrifies its characters and audiences at the deepest level of all: shattering their foundational understanding of the world.

Carpenter is an excellent craftsman at putting you in a zone of discomfort with words and pictures, but he becomes a True Master when he combines those skills with his final gift — as musical composer. He is the rare director who can express the language of cinema in its totality: word, picture, sound.

They Live was released right when I was on the cusp of adulthood, and its message was perfectly timed. Gen-X humor already had me primed to question forms of authority, but those kinds of questions were usually local, individual, and drastically smaller in scale. Parents, teachers, and preachers, yeah, to know they were either, at best, flawed vessels, or, more likely, completely full of shit, was manifestly evident and a fact of life that me and my peers put up to ridicule on an ongoing basis. But questioning everything — the basic assumptions of the world, our sources for input, our values — this was a new perspective.

Nada, the main character portrayed by Roddy Piper, is initially resistant to having his worldview challenged. He’s smart, observant, but in spite of all the evidence to the contrary (his former city decaying with closing factories, his new city overrun with a homeless encampment, his employment opportunities dwindling), he says:

I deliver a hard day's work for my money. I just want the chance. It'll come. I believe in America. I follow the rules. Everybody's got their own hard times these days.

But he’s no fool. His curiosity and economic desperation lead him to discover a new truth about the world.

And he’s nobody’s slave, either. He’s got no plan, no inhibitions, and no circumspection. He’s brash, reckless, and easy for banal evildoers to identify him as a threat.

I’ve got one who can see.

That’s the moment. Right there. It’s probably the best any of us can ever achieve in this life. The movies are filled with stories of heroes who overturn an evil system: from historical dramas, to space fantasies, or dystopian sci-fi thrillers like They Live. Sure, we’d rather be the swashbuckling hero, delivering the coup-de-grace felling the tyrants of the multiverse, and celebrating accordingly. As Conan once said what is best in life is to crush our enemies, see them driven before you, and to hear the lamentations of their significant others*.

But that’s not in the cards for most of us, is it? The best we can hope for, on brief occasions, to confront those systems of control - stare them right in their beady eyes - and inspire fear in their foot soldiers or middle-managers, right before they vanish like the cowards they are.

Sure, I’m there for the revolution, if it comes. Sign me up. But before we can get there, more of us need to see.

Be one who can see.

*Conan may have used less politically-correct phrasing, but this could merely be the result of translation error from the original scrolls of the accounts of the great barbarian.

When We Were Kings

This is the movie that changed the documentary genre for me. This wasn’t just some sterile snooze-inducing study of a topic; it had the full complement of cinematic tools at its disposal: action, tension, drama, a pulsating soundtrack with the mighty gloved hands of Muhammad Ali and George Foreman providing the heavy beats for the percussion section…

…and a poetic protagonist:

I done ‘rassled with an alligator

done tussled with a whale

I done handcuffed lightning

thrown thunder in jail

Sometimes the best art is the result of an accident.

When We Were Kings started out a music documentary about Zaire 74, a three-day live music festival in Kinshasa. Oh, and there was also supposed to be some fight going on. Maybe they could capture some footage from that for additional flavor?

And then the filmmakers happened to be there at the pivotal moment that changed the film, and perhaps, boxing history: Big George Foreman accidentally got caught by a sparring partner’s glove at a sharp angle, cutting his eye, delaying the fight for six weeks. Leading the music-fest documentarians to wonder: Hey, maybe we should shoot some more footage about the fight itself since we’ve got all this extra time?

Sometimes the best art is the result of adversity.

It took twenty years and several iterations of the film to arrive in its final form. Since it was a low-budget film meant to cover an obscure music festival, the price of converting the raw film footage into tape for editing was too prohibitive to get it immediately edited, so the footage sat in vaults for years that became decades. As the project took so long to materialize, a new incarnation was birthed. A film about a music fest became a boxing film focused on Ali. Then a preliminary version was shown at festivals and it transformed into the stunning work it was destined to be—one that combines the infectious music and the charismatic characters, put into context by narrators whose analysis elevates our understanding of the events.

The film is a time travel ticket to the front row: decades of unseen footage brings to the present moment one of the most legendary spectacles in sports history, The Rumble in the Jungle. The delay in production opened a vessel to re-examine these figures with footage that had incredible intimacy gained through its low-budget non-intrusive presence in the moment it was originally filmed. Combine that intimate feel with the years of distance providing an accumulation of knowledge on the people and events to allow for superior analysis to guide the experience through the raw footage.

When I was a kid, there were only two things we could count on: Evel Knievel would jump over anything, and Muhammad Ali would knock out anyone. One comic book even placed Superman in the ring with Ali, and, at first glance, seemed like a fair fight.

When We Were Kings was part of a revolution in documentary filmmaking in the 1990s, where the rigid unwritten “rules” of the form were bent and broken. Gone were the illusions of detached objectivity and clinical observation. When We Were Kings places you in the blistering heat of Zaire in 1974, bouncing between the music festival, the workout gym, and the ultimate prize fight at the film’s culmination.

The build-up to the fight is pushed by the intoxicating rhythms of the the live music provided by the likes of James Brown, Bill Withers, B.B. King, and The Spinners. The sweat-drenched energy of the festival provides an anticipation for the main event — which does not disappoint.

Kings demonstrates the enduring power of sport: here we see writers George Plimpton and Norman Mailer re-live the fight decades later in stories they’ve been telling for half their lives, but their enthusiasm and passion are so palpable it feels as if Mailer is about to reach through the screen and grab you by the collar.

When I see the historic footage, I cringe at the fact that one of the United States’ lower moments—convicting Ali of draft evasion and denying the sincerity of his conscientious objector status— took place at a courthouse in my home town of Houston. Ali, and the sport in general, had the prime years of his career stolen.

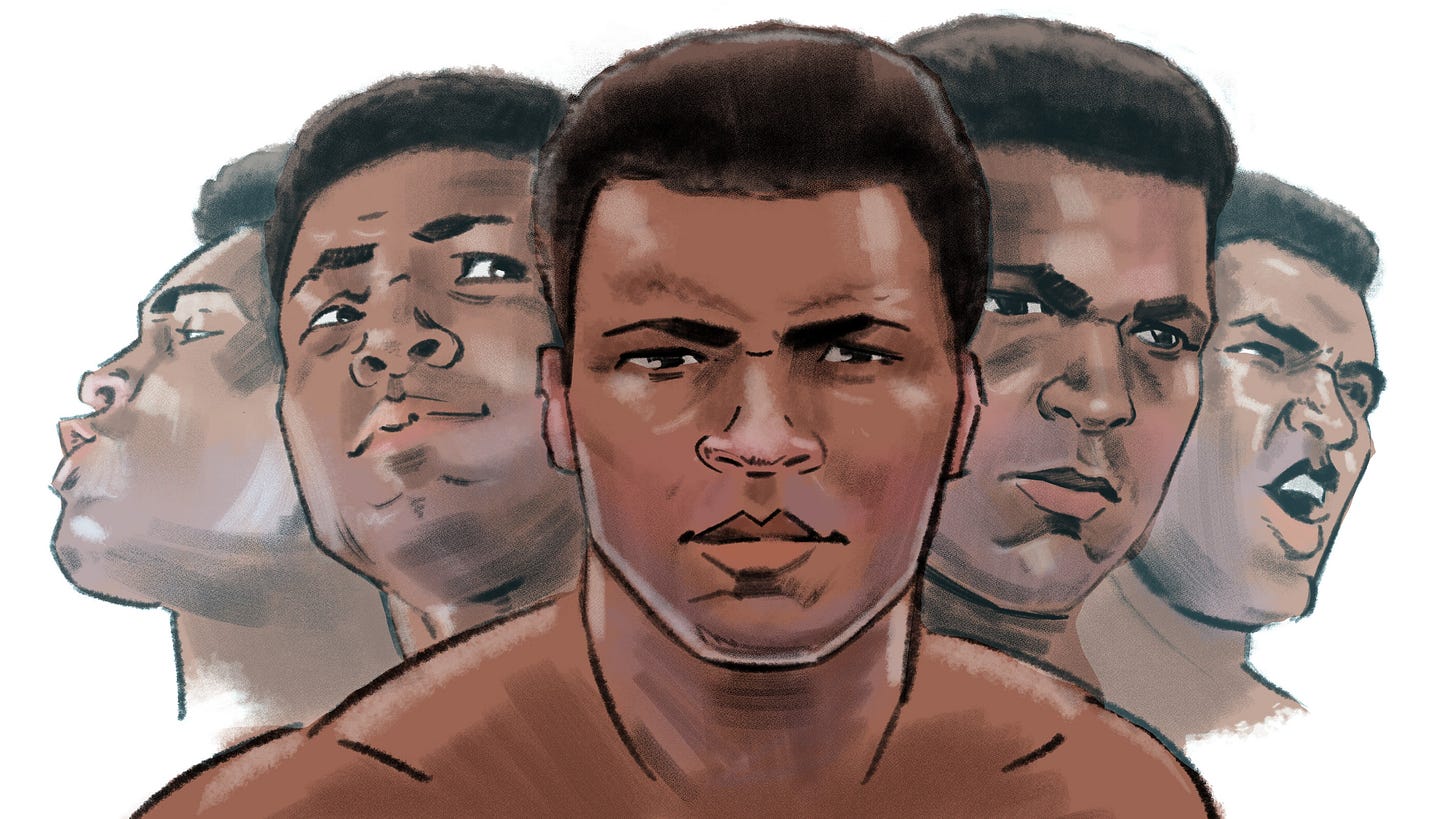

The filmmakers managed to capture the many faces of Ali: The prize fighter. The anti-war protestor. The rhyming raconteur. The charismatic figure who commands the attention of everyone in every room he walks into. But the most unexpected face of all was the face of fear. Norman Mailer’s analysis focuses on a powerful but subtle moment early in the fight. Ali’s risky first-round strategy proved a failure, resulting in Ali having to face his darkest moment: a seemingly invincible opponent whom he had no clear means of victory against.

Some of the most inspiring footage of Ali in the film is not any depiction of his athletic prowess, but rather his statements on political and spiritual matters. With verbal dexterity just as impressive as his jabs and footwork in the ring, Ali could confront the topics of poverty, prostitution, drugs in black neighborhoods. He had a social conscience the likes of which most of today’s pro athletes who view themselves as brands and walking corporations do not have the courage nor inclination to try to follow.

And when everyone doubted Muhammad Ali - perhaps himself most of all - he would riff on how his connection to the people of Zaire and his faith in Allah would energize him and summon the power of the crowd to chant:

Ali, bomaye! Ali, bomaye George Foreman!

(Ali, kill him, Ali kill George Foreman!)

And it would be through their collective spirit that he would prevail.

The film’s editing and use of multimedia—music, narration, film and still photography—recreate the ratcheting tension of the fight, and no matter how many times you see it, the utter shock at the miraculous outcome is surprising every single time.

George Plimpton covered many fights in his time as a sports writer, and at boxing matches he said he would feel enormous sympathy for the loser in a fight. He said these fighters seem as titanic figures but then are greatly diminished in defeat. But in this case, with the passage of time, any diminishment of the previously frightening and obstinate bully George Foreman is lessened by our knowledge of his transformation into the affable and delightful gentleman who regained the heavyweight title at age fifty and whose hamburger grills are now in millions of American kitchens.

But it is the knowledge of what came next for Ali that adds poignance to the fleeting glory captured in When We Were Kings. Yes, he was vindicated. Yes, it was a boxing miracle. That joy is tempered by the knowledge of the brutal Parkinson’s Disease which would afflict Ali for the second half of his life. But for the 89 minutes of this film, we get to relish the audacity, the one-of-a-kind-ness, the man who was simply called The Greatest.